Alone Together

Sanctuary, Privacy & the Workplace

By Chelsia Sooksengdao

Imagery taken from honors capstone at the University of Arkansas, Refuge for the Refugee.

With Mental Health Awareness month coming to a close, it’s important to acknowledge the overlap of psychology and architecture as tools that can improve mental wellness in workplace design. In the words of Alain De Botton from The Architecture of Happiness, architecture can be “not only physical but also psychological sanctuary”.

Given that it has the power to properly and positively influence the psychology of an individual, questions designers regularly grapple with are: how can psychological stress be reduced through thoughtfully designed workspaces, and can these environments become a sanctuary of social wellness?

Considering pandemic-influenced design trends, the need for office spaces to flex with our comfort level, moods, and meeting requirements has only become more relevant. By investigating aspects of social psychology and proxemics, we can connect these concepts to spatial solutions, with the goal of reducing emotional stress and improving mental wellness conditions in the workplace.

Social interactions and wellness in the workplace can be strongly influenced by the physical environment. Open spaces bring people together and lead to more collaborative work, while private spaces offer a physical boundary between the user and external distractions. Both spaces are necessary, but one without the other can result in an unhealthy balance.

Studies show that in male-dominated open office workplaces, women are more likely to feel observed, watched, and scrutinized, with no space to find privacy. This sort of “ambient sexism” can promote staring, comments on clothing, makeup, and facial expressions. With the rise of open office layouts, offices that lack choice-based design can result in emotional stress at work. People can feel as if they have no privacy or personal space.

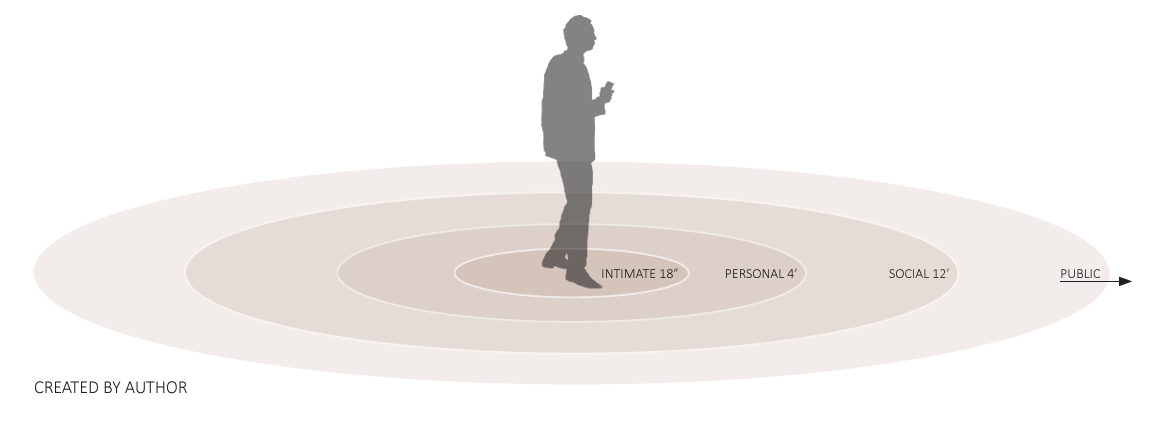

The concept of personal space is understood as the zone around an individual that warrants protection from stressful stimuli. It is an area where an individual feels safe from potential aggression or stressors, and can vary from person to person, or day to day. This personal space is naturally sought by the human being, and is subconsciously shaped and delineated by the brain. When it is violated or unattainable, it deeply affects the individual’s psychological stability and comfort.

This idea is reflected in the rise of wellness rooms and phone booths in workplace design. In order to design for healthy interactions, we must give back territorial control and autonomy to the worker.

Wellness rooms are a great place to start. They provide a space for sanctuary, where personal autonomy, emotional release, self-evaluation, and protected communication can be expressed in private. Phone booths are another way workers can access privacy. By taking calls behind a closed door, the anxiety some may feel during those moments can be reduced. The smaller space also provides a sense of security and comfort, and a contrast to the open office.

Eastlake Studio Wellness Room

At Eastlake Studio, we recently developed a plan for our own wellness room. The simple design allows one person to have a quiet place to work, nap, pray, meditate, or just decompress from a stressful situation. A comfortable chair, dark finishes, and custom wallcovering help to create a serene mood within the larger, often bustling studio. Last year, Eastlake also installed two ROOM pods to increase the quiet spaces available beyond the three built-in phone rooms. These private and semi-private spaces give staff a quiet refuge for important calls and focus work.

“The significance of architecture is premised on the notion that we are…different people in different places - and on the conviction that it is architecture’s task to render vivid to us who we might ideally be.”

- Alain De Botton from The Architecture of Happiness